在此处更改您的语言和 LGT 位置。

私人客户的数字平台

登入 LGT 智能银行

金融中介机构的数字平台

登入 LGT 智能银行 Pro

常见问题解答 (FAQ)

LGT 智能银行帮助

常见问题解答 (FAQ)

LGT 智能银行专业版帮助

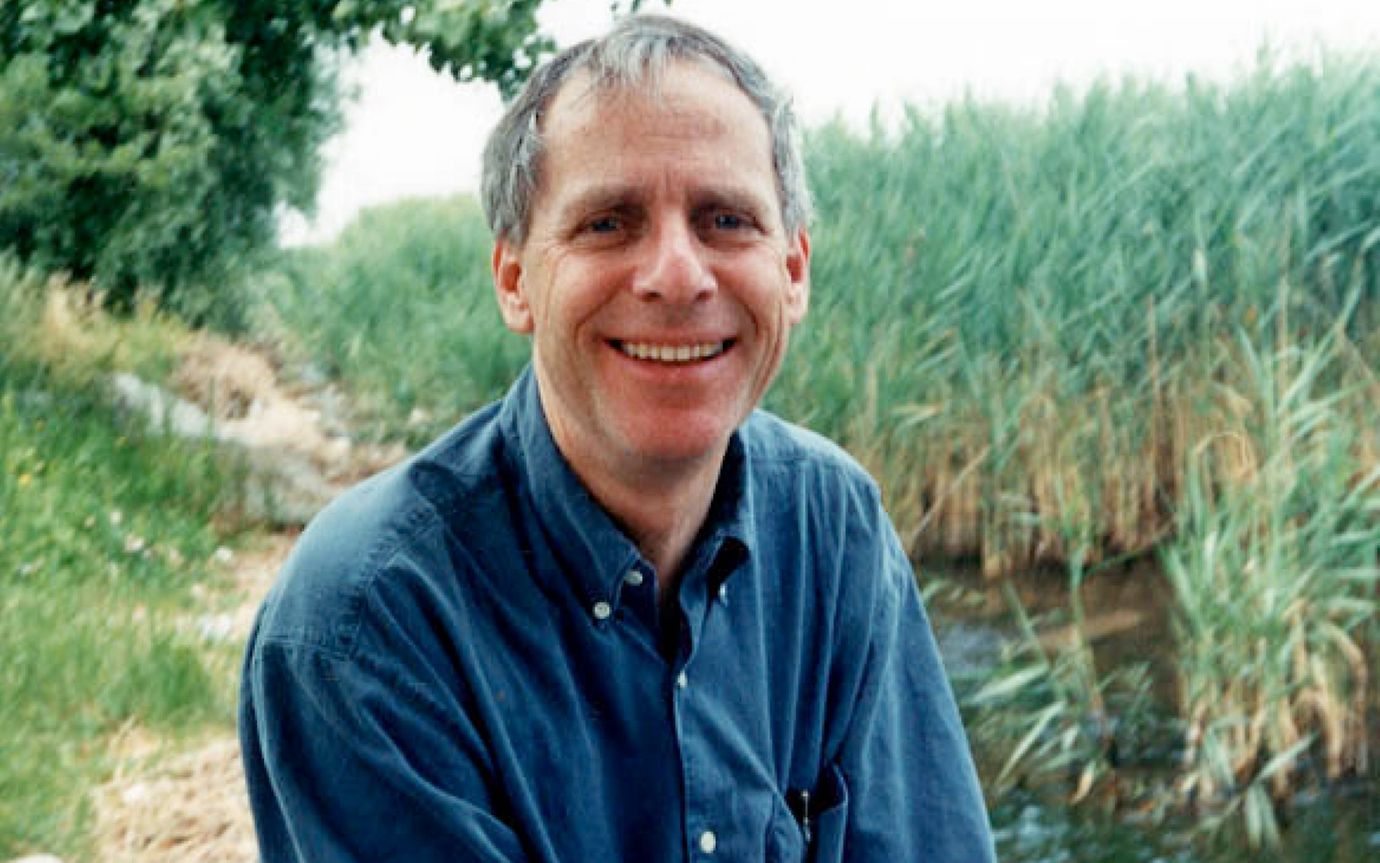

The Israeli cognitive psychologist not only revolutionised his own academic discipline but had an outsized influence on economics through his theories on heuristics and loss aversion.

If you've ever wondered why people make irrational decisions when considering, for instance, how to invest, you are not alone. An entire strand of economic thought emerged last century to explain why investors (and others) don't behave rationally when forced to make decisions in uncertain situations. Traditional economic theory operates under the assumption that humans are motivated by material incentives and make decisions rationally. It took a couple of psychologists to turn this notion on its head.

Behavioural economics developed out of experimental research that showed that people don't actually make decisions based on the laws of probability. It also proved that they generally put more emphasis on risks than on benefits, and that the human reasoning process involves many more twists and turns than previous economic and psychological theories had proposed. This research was conducted by the Israeli psychologist Amos Tversky, together with his long-time collaborator Daniel Kahneman in the 1970s. Their discoveries influenced not just psychology and economics, but finance, law, and international relations as well.

Amos Tversky (1937-1996) taught at Stanford University in the USA for nearly two decades until his untimely death aged just 59. During his career he forged an international reputation as a cognitive and mathematical psychologist. His early work had a distinctly mathematical cast, shown in the influential "Foundations of Measurement", a three-volume textbook series that established the formal foundations for measurement in the sciences, which Tversky co-authored. This theoretical and highly abstract work is no guide to his later focus.

What changed the course of Tversky's life - and that of economics - was his collaboration with another Israeli psychologist, Daniel Kahneman, when both were working at the Hebrew University in the early 1970s. A more unlikely pair would be hard to find, both in terms of academic interests and personalities. Tversky was outgoing, optimistic, and ebullient; Kahneman, reserved, serious, and pessimistic. In academic terms, Tversky was the theoretician, while Kahneman focused more on the empirical and the real world.

Yet their collaboration was endlessly fruitful. When Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in economics in 2002, his acceptance speech and the associated press coverage all acknowledged the contribution of Tversky. Had Tversky not died in 1996, it would have been a joint prize, but Nobels are only given to the living. That an economics Nobel was awarded to two psychologists underscores just how influential their work was in what many consider an unrelated field.

Tversky used the term "Prospect Theory" for the initial studies he carried out with Kahneman on how people manage risk and uncertainty. It's a memorable title and their paper, published in 1979 in the journal "Econometrica", laid the groundwork for most of their later theories and experiments on decision making.

Key among their findings were their somewhat counterintuitive discoveries on loss aversion and risk-seeking behaviour. It turns out that people have quite different attitudes to loss than they do to gains. When given a choice between receiving USD 1000 with certainty, and a 50 per cent chance of receiving USD 2500 (which also means a 50 per cent chance of getting nothing), more people choose to receive USD 1000. This is because losses hurt considerably more than gains.

Thinking becomes considerably more muddled if the choices are more ambiguous. When the same people are confronted with a certain loss of USD 1000 or a 50 per cent chance of a USD 2500 loss, they more often chose the second, riskier alternative. It turns out that people confronted with the possibility of recouping a loss do not act rationally. This risk-seeking behaviour runs counter to what might have been expected and is a cornerstone of Prospect Theory.

Another observation that was part of their early research was the tendency of people to see patterns and make connections where none exist. Take for instance their poker chip test. Two bags are filled with the same number of poker chips. In the first bag, two-thirds of the chips are red, and the rest are white. In the second bag, the opposite is true.

If ten chips were pulled from the first bag and eight were red, while 30 chips were taken from the second bag and 20 were red, most people would say that the first bag was more likely to have more red chips because 80 per cent of the chips were red. While this may be, as it is here, the right answer, it isn't the rational one. Statistically speaking, it is more likely that the second bag has the majority of red chips, because the sample size is larger, and therefore more reliable.

Although much of Tversky's work focused on the individual, Prospect Theory is especially applicable to the work of financial economists, who are concerned with the working of capital markets. Over the years, Tversky's ideas have led to investigations by financial economists around the world concerning the effect of time, uncertainty, options, and information on the behaviour of markets.

Throughout his career, Tversky continued to back up his theories with research and experiments. This is common practice in psychology, but not so usual in the world of economics, since neoclassical theory is based on the idea that people behave rationally in their own self-interest in the absence of constraints. Economists latched onto Tversky's empirical work to develop what became known as behavioural economics, which seeks to explain more fully how people behave in reality rather than in theory.

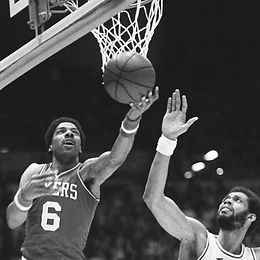

One of Tversky's later, and best-known studies, is called the "hot hand" experiment. Fans and coaches often believe that that players have "hot streaks", where successful shot after successful shot makes the next one even more likely. Here he showed that contrary to popular belief, there is no likelihood (and indeed less likelihood) that a basketball player who just made a shot would also win with the next one. Tversky analysed every shot taken by the Philadelphia 76ers over 18 months to demonstrate the fallacy of the "hot hand".

This idea of the "hot hand" is an example of how people bring their own preconceived perceptions of probability to decision making. In reality, statistics show that a few successful hits are no guarantee of future success. Although some of these examples may seem simplistic when compared with the difficult decisions facing investors, they have provided rich food for thought both for researchers who have used them to design more complex decision problems, and for investment professionals seeking successful outcomes for their clients.

Tversky's work convinced economists and other social scientists to pay attention to what people actually do when presented with decisions, rather than focusing on what people would or should do if they behaved rationally. In this way, Tversky's ideas continue to influence not just social scientists, but also investors all over the world.