在此处更改您的语言和 LGT 位置。

私人客户的数字平台

登入 LGT 智能银行

金融中介机构的数字平台

登入 LGT 智能银行 Pro

常见问题解答 (FAQ)

LGT 智能银行帮助

常见问题解答 (FAQ)

LGT 智能银行专业版帮助

Conferences such as COP 27 are not a major driver in the fight against climate change, says climate physics professor Reto Knutti. Why he is still hopeful for the future.

As the COP 27 UN climate change conference in Egypt draws to a close, Reto Knutti looks on from his office in Switzerland with a mix of weary déjà vu and cautious optimism. As a physics professor and leader of the climate physics group at ETH Zurich, Knutti, who is 49, has devoted a career to researching the effects of a slow-motion crisis. He knows hot air when he sees it.

“These meetings are important as a platform for exchanging ideas and agreeing on common goals, and of course they were critical in establishing the Paris Agreement,” says Knutti, a former key member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). “But honestly, since then, not so much has happened. And it's probably going to be the same this year.”

Knutti says the world should have transitioned to a new phase since the Paris conference in 2015, when nations agreed to a target of keeping the rise in average global temperatures to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels – and preferably below 1.5°C. “It now comes down to the countries to do their homework,” he says. “All the countries must come to net zero emissions sooner or later, and that's done by national politics and laws and technology, and we shouldn't expect that the COPs are going to be a major driver of that.”

Naturally, Knutti is a keen follower of Switzerland's own progress in honouring global commitments. And he isn’t impressed. Like many countries, Switzerland has set out to become climate neutral by 2050 rather than a more ambitious date of 2030. A study published last month by the Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW) suggested that if the rest of the world followed Switzerland’s example, it would only be possible to limit global heating to 1.7°C.

One of the most visible themes of COP27 has been the debate about what is known as “loss and damage” – the financial assistance that poorer, more urgently affected nations are asking bigger economies to provide. There has been resistance to such an idea, which was part of the Paris Agreement, even among some progressive developed nations such as Sweden.

Knutti sees value in the principle of reparations, and in honouring the pledges made in Paris. But he is aware of the complexities of such a system. “The question is, are you actually going to get the money to the relevant places and people,” he says. “And is just simply money going to help, or should we be going there and trying to do the actual projects and building capacity?”

Meanwhile, back at home, Knutti is keenly aware of the immediate effects of rising temperatures. The past year has been a disaster for the world’s glaciers. Shortly before COP27, UNESCO, the UN’s educational, scientific and cultural organisation, published a report showing that a third of the 18,600 glaciers identified at its World Heritage sites are expected to disappear by 2050.

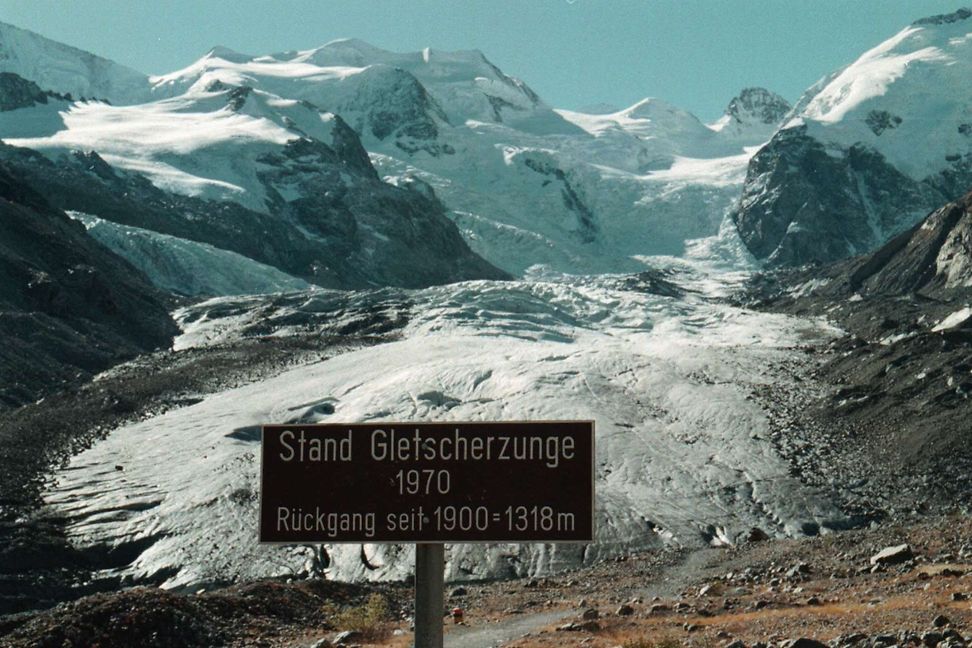

Swiss glaciers recorded their worst rates of melting since records began more than 100 years ago. In total they lost 6% of their volume, nearly double the previous highest loss, recorded in 2003. “Some of the biggest glaciers have lost six metres in thickness, and that’s above 3000 metres in altitude,” Knutti says. “It’s remarkable.”

While Knutti says Switzerland’s water supply is relatively secure, glacial retreat elsewhere threatens life and livelihoods. Yet it all pales in comparison with the melting of the polar ice sheets, which have also had a bad year. Glaciers do have a potent symbolic function, however, as disappearing ice that we can actually see rather than distant ice sheets that may as well be on the moon. “I think glaciers are the most visible sign of what is happening to our climate,” he says.

Perhaps more visible still since the last COP conference has been the rise of more direct action against climate change. Groups such as Just Stop Oil have taken the fight to the streets, and the airports, causing disruption as activists seek to bring roads and cities to a stop. Meanwhile, prominent buildings and works of art are also being targeted.

While obviously sharing their goals, Knutti takes a sceptical view of these apparent new tactics. “If you read the literature, there is really no consensus on the effect of those things,” he says. He also fears that making people angry risks leading to an even more divided politics. “We need to solve this problem by getting together and finding solutions that people can agree on, rather than trying to fight even harder.”

Despite all of the threats and challenges the world faces, and the relative inaction at COPs since 2015, Knutti does see glimmers of light. “I think we’re starting to see that countries and companies are moving forward without waiting for others to do something, or waiting for new taxes or regulations, because they see the economic benefits of shaping a transition,” he says. “For a very long time change was seen as a burden, but I think now it can be seen as an opportunity, and that makes me somewhat hopeful that things are moving in the right direction.”