在此处更改您的语言和 LGT 位置。

私人客戶的數碼平台

登錄 LGT SmartBanking

金融中介機構的數碼平台

登錄 LGT SmartBanking Pro

解答常見問題 (FAQ)

LGT SmartBanking 幫助

解答常見問題 (FAQ)

LGT SmartBanking Pro 幫助

Inflation is unavoidable, but is there a level we can live with?

Recent inflation hikes in the US and Europe have raised concerns that we may be entering a period of prolonged high inflation. Although inflation has come down from the heights of last year thanks to aggressive interest rate rises by the central banks, this doesn’t necessarily mean we’ll return soon to the low inflation levels of the past few decades.

Nobody likes inflation, but just as death is an inevitable part of life, so too is inflation an inevitable component of the macroeconomic cycle. But what causes inflation? And what is its role in the economy?

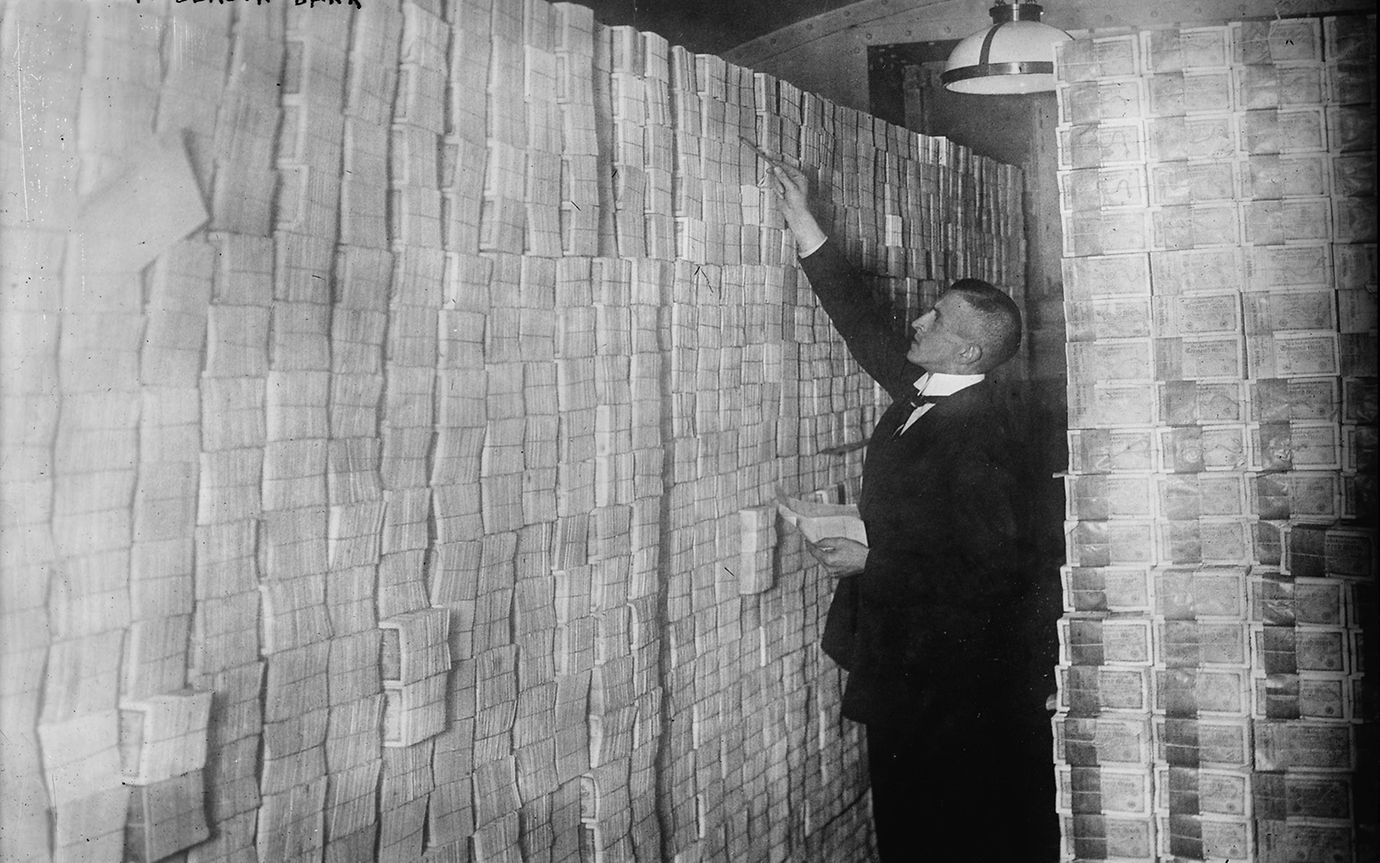

Put simply, inflation is an increase in the prices of goods and services, meaning that consumers need to spend more money to get the same goods or services. Inflation occurs when the money supply rises to the point where there is "excess" cash.

This excess money supply creates excess demand for goods and services. When there’s a lot of money, or liquidity, people and companies can keep raising prices, even substantially, and still have no trouble selling to consumers. Prices keep going up until customers are no longer willing (or able) to pay, at which point there's no longer an excess money supply.

A cunningly hidden form of inflation is known as shrinkflation, when producers quietly reduce the size or quantity of a product, while keeping the price the same. It’s effectively a price rise by stealth. Another twist on this is dubbed skimpflation, when cuts to services or quality achieve the same effect: customers pay the same, but get less.

Deflation is a decline in the price of goods and services; it’s the opposite of inflation. Deflation is not to be confused with disinflation, which is a slowing in the rate of inflation. So there’s still inflation, but it’s slower.

Stagflation is the combination of high unemployment, or stagnation, with rising prices, or inflation. The term was coined in the 1970s when there was a lot of both.

Inflation can also come from disruptions or shocks to supply and demand. During the early days of the pandemic, there were sudden supply-side shocks as governments forced businesses and factories to close, which reduced production. In 2022, the war in Ukraine shocked the energy supply, as well as grain exports, which led to hugely inflated prices. The demand side has also seen recent shocks as people lost work because of the pandemic, while others, stuck in lockdown, had to cancel trips, stop dining out, and generally reduce their spending.

For as long as there's been money and trade, there's been inflation. What's changed is our understanding of and ability to manipulate it. In ancient times, the Roman Empire experienced massive inflation during the third century, estimated to be around 15,000 percent annualized. Roman rulers relied on gold and silver mines, or looting and taxing conquered enemies, to add to their coffers.

Romans didn't understand the price dynamics

But as the empire grew, so too did spending, eventually outstripping Rome’s ability to import gold and silver. With no debt market in existence yet, the only two options were to increase taxes or debase the currency by lowering the amount of precious metal in the coinage. The combination of a debased currency and continued inflows of gold and silver increased the money supply. The consequence: massive inflation.

"Back then they didn't have a clear understanding of the price dynamics of the money supply...so they didn't know what was happening," says Pierangelo De Pace, Professor of Economics at Pomona College in California. Not realizing that the increased money supply was causing inflation, the Emperor Diocletian looked for human culprits. He blamed widespread greed and ordered the decapitation of profiteers and speculators. He also set price controls. These extreme measures ultimately lowered inflation because they disrupted the production of goods – but they also resulted in a recession.

Fortunately, economists have more sophisticated, less lethal means to control inflation these days. The two favored tools used by central banks are controlling the money supply by buying and selling bonds, and raising or lowering interest rates to influence borrowing, growth, and employment levels. Interest rates and the money supply are interconnected: when interest rates go up, the money supply declines and vice versa.

During the pandemic, governments spent trillions on relief checks for individuals and businesses, and lowered interest rates to stimulate borrowing. All this extra money in the economy, combined with shocks to supply and demand, meant countries saw inflation rise to levels not seen in decades. In response, central banks have been raising interest rates to curb borrowing and spending.

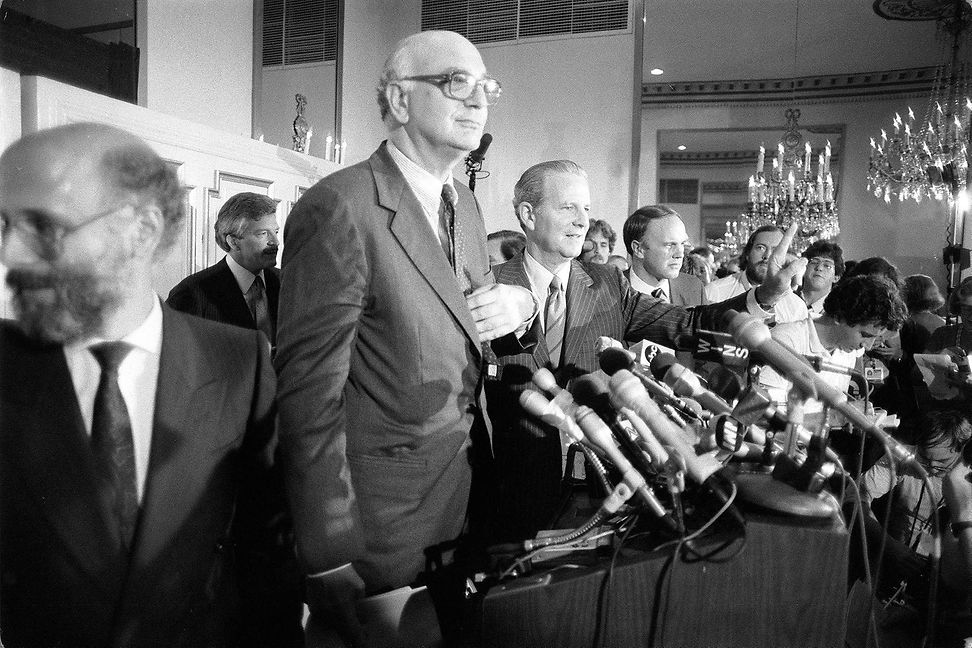

Both inflation and interest rates are modest now compared to the 1970s and 80s. During the 1970s, when US inflation was almost 15 percent, and the UK rate hit 25 percent, it seemed inflation would increase every year. To stop this and curb the money supply, Paul Volcker, then Chairman of the Federal Reserve, gradually raised the federal funds rate to 20 percent and the prime rate to over 21 percent. These moves were painful and led to stagflation, which is a nasty combination of high inflation, slowing economic growth, and rising or high unemployment.

As if the economy has broken its bargain with society

Though there are many comparisons to the high inflation of the 1970s, the causes and inflation rate this time around are different. Economists and market watchers hold out hope that higher interest rates will lead to a soft landing, as opposed to a long and difficult recession.

"To keep aggregate demand equal to potential supply, and to keep the economy at full employment and without inflation, it's this delicate dance that they attempt to do," explains Bradford DeLong, Professor of Economics at the University of California at Berkeley and former Deputy Assistant Secretary at the US Department of the Treasury during the Clinton administration.

While inflation has gone up and down over history, what hasn't changed is our dislike of rising prices. Inflation can be extremely disruptive to society and governments. "It gets people unhappy and it annoys them. People believe that the economy is running in a certain way and thus they'll be able to buy what they usually buy with their usual income. And they go out to do that and find that they can't...It's kind of broken its bargain with them," says DeLong.

Because inflation disrupts everyone, central banks try to keep it as low as possible, ideally close to zero. Since the 1990s, central banks in western economies have maintained a 2 percent target for inflation. The idea started in New Zealand, which experienced a period of high inflation during the 1980s and wanted a way to lower inflation expectations. These expectations are crucial for determining actual inflation because expectations get written into contracts and price and wage increases. Initially adopted in New Zealand, the 2 percent target was soon picked up in other western markets.

Economists reasoned that a 2 percent target is close enough to zero that price increases don't feel onerous but still create some wiggle room for central banks to cut interest rates to stimulate the economy when needed. In Japan, which has fought deflation, experienced as a fall in the overall level of prices for 30 years, interest rates are actually below zero. But this doesn't give any wiggle room to stimulate demand by lowering interest rates further.

When modest, inflation isn’t a bad thing. Slight inflation can encourage demand. Here's an example: If you think the new car you want to buy will be more expensive next year, you’ll buy it sooner rather than later. If prices are in decline, however, you’ll often hold off making a purchase because the longer you wait, the lower the price will be. These expectations – and purchasing decisions - ultimately affect the overall economy.

"The equilibrium is very difficult to strike, but these are dynamics that are always kept in mind by policymaking entities every time they have to decide whether inflation is more acceptable than deflation. The conclusion overall is that we'd rather have a moderate level of inflation, 2 percent or 3 percent, than full-fledged inflation," declares De Pace.

Because inflation raises the prices of goods and services year after year, USD 1,000,000 in your account 20 years ago wouldn’t give you the same kind of purchasing power today. So how do you calculate the impact of inflation? There’s an equation for that.

It starts with looking at the Consumer Price Index. Government statistical agencies measure inflation by creating a basket of goods and services used by households. This is the Consumer Price Index. In the euro zone, the European Central Bank publishes the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices. Countries in the European Union follow the same methodology, so countries can be compared with each another. In the US, the Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, or the CPI-U.January 2003: CPI-U = 184

January 2023: CPI-U = 299.170

Amount x start period CPI-U ÷ end period CPI-U = value of current dollars

USD 1 million x 184 ÷ 299.170 = USD 615,035

To calculate the value of past dollars in current dollars, make a small switch:

Amount x end period CPI-U ÷ start period CPI-U = value of past dollars

USD 1 million x 299.170 ÷ 184 = USD 1,625,924

This shows that it would take almost USD 1.63 million today to have the same buying power as USD 1 million did in January 2003.

There are inflation calculators online that will calculate this for you. Simply select the country and years involved. (For the US , you can also use this official calculator.) Why does this matter? Because it’s vital to keep inflation in mind when laying out long-term financial plans, such as monthly income in retirement.