在此处更改您的语言和 LGT 位置。

私人客戶的數碼平台

登錄 LGT SmartBanking

金融中介機構的數碼平台

登錄 LGT SmartBanking Pro

解答常見問題 (FAQ)

LGT SmartBanking 幫助

解答常見問題 (FAQ)

LGT SmartBanking Pro 幫助

Once the engine of European economic growth, Germany's stuttering economy reflects fiscal risk aversion, energy challenges, and insufficient digital flexibility. Yet a strong industrial core, a growing green tech sector, and falling inflation all hold out hope for a longer-term recovery.

There's no denying that the German economy is in a difficult position. With the slowest growth rate of any Eurozone economy in 2023, and weak prospects for recovery in 2024, Germany has been hovering on the edge of recession. The reasons for this situation are many and varied - and not easily reversed.

But as the world economy slowly shows signs of recovering, Germany too may begin to regain its strength. Globally, inflation is cooling, consumer confidence is reviving, and interest rate cuts are likely soon.

The critical issue, explains Wolfgang von Hessling, chief economist for EMEA at LGT Private Banking, "is whether German politicians necessary to not only help the underperforming economy to trend growth, but also to lift that trend growth potential out of its structural weakness.

Germany fell asleep at the wheel - literally

At the forefront of the problem is the slump in German industrial output. What has now become apparent is how deep-seated the loss of German competitiveness is. "These economic doldrums are not just reflective of a short-term issue," says von Hessling. "German industrial growth has been shrinking by an average of 1.5 per cent year-on-year for five years now."

This situation existed before the pandemic, before the Ukraine war, and before the extraordinary rise in energy costs. "Germany fell asleep at the wheel, literally," states von Hessling. Investment has not kept pace with developments in production techniques and digitisation. Long known as an industrial powerhouse with cutting-edge engineering and immense factories, Germany did not take advantage of the cheap funding available after the global financial crisis, and thus failed to ensure its competitiveness.

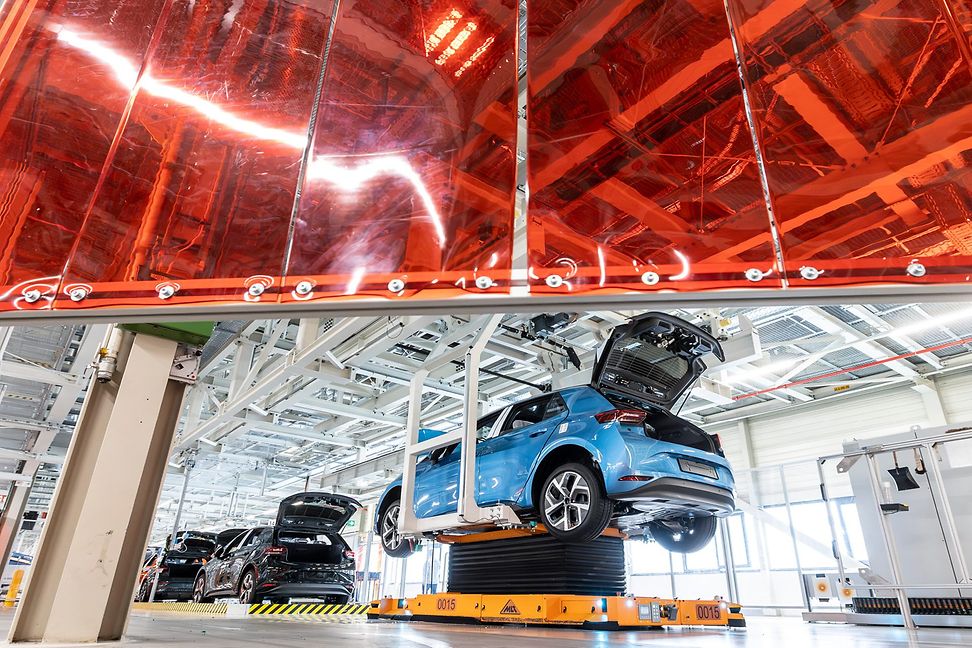

In the automotive sector, Germany has fallen far behind the USA in terms of the development and sales of electric vehicles. It's also seeing the effects of increasing competition from fledgling Chinese car manufacturers.

One place where German engineering continues to shine is in the adoption of green technology. The German government has made an enormous commitment to weaning the country off fossil fuels. This has meant significant investments in renewables to enable the switch to a zero-carbon economy.

Although hugely welcome in a country that found itself far too reliant on Russian natural gas when the Ukraine war started, the delivery of renewable energy requires an entirely different energy infrastructure to that used by oil and gas. Since Germany does not yet have this in place, it's proving difficult to replace imported gas with competitively priced domestic renewables. So the goal of a sustainable, safe, and cost-effective energy supply is still a long way off. With energy prices dropping, the political will to achieve zero carbon may be declining too.

German politicians appear to be aware that the need for structural reform is urgent. However, an attempt to redirect EUR 60 billion of unused coronavirus budget to Germany's Climate and Transformation Fund (KTF) to use for industrial modernisation and the green energy transition was blocked by the Federal Constitutional Court last November. This produced an EUR 17 billion hole in the 2024 budget, and the resulting fiscal freeze means that funding for promised microchip and battery factories, as well as for many other modernisation projects, is on hold.

While the revitalization of German industry will take political will and a lot of money, it isn't an entirely negative picture. The "Mittelstand", made up of independent, often mid-sized and small firms that employ 60 per cent of German workers and account for the largest share of the country's GDP, are still punching way above their weight in terms of market share and export capabilities.

Often university spinoffs or family firms, these companies are somewhat protected from the stock-market pressures of short-term profit maximisation, and have been the source of great engineering innovation for decades. "This is a sector with deep roots in the German economy that could be reinvigorated with the right incentives," notes von Hessling.

Germany's notoriously paper-heavy bureaucracy is one of the biggest bugbears for industrialists.

One place to start would be with Germany's notoriously paper-bound bureaucracy. Cutting through the red tape and digitising properly would address one of the biggest bugbears of German industrialists.

But equally important, and perhaps sometimes overlooked, is the wider reliance on regulation. Taxes are high. Government borrowing is constrained. There's a skills shortage made worse by full, but not always productive, employment. Loosening the bonds of fiscal restraint could jumpstart long-delayed investment in deteriorating physical infrastructure like roads, rails, and schools.

Visible changes could prompt the return of consumer confidence, eroded in recent years by rising energy prices and inflation. The elevated level of the German stock index, the DAX, currently close to historical highs, does indicate that pessimism may have reached its lowest point, and confidence can rise again.

"In Germany, the fiscal reaction to corona was relatively weak, certainly in comparison to the US. That's one reason why consumer spending remained more buoyant in the US," explains von Hessling. "I don't want to call a bottom on consumer pessimism in Germany, but the worst may be behind us." It's also true that consumer behaviour is more important in the US. Consumption drives two-thirds of the US economy, whereas in Germany, consumption makes up merely half the country's GDP.

Finally, the overall European economic environment may support a return to growth, even if rather slowly. Inflation has dropped sharply and looks like it will continue on a downward trend. The European Central Bank is forecast to cut rates later in the year. "The cuts may be more aggressive in Europe than in the US," says von Hessling, "which would be positive for German investment activity."